As Ontario slashes total spending to tackle the deficit, it appears that libraries did a poor job briefing the new government. Ironically, the library cuts undermine the efficiency objectives of the Ford government.

As a user of the Niagara on the Lake Public Library, I was startled at the announcement that cuts in the 2019 Ontario budget would end the service that provides delivery of books between library systems. When I check whether a book is at the library, if it’s not in the local collection, there might be a copy at another library in the Niagara region (such as Fort Erie or Pelham). With the click of a button, I can place a hold on the book. When the book becomes available, it gets shipped between the library systems, and I can check it out in NOTL. After I return the book to the NOTL library, it gets shipped to its home library or the next patron.

The operation that transfers books between libraries, called inter-library loans, has been run by Southern Ontario Library Services (SOLS). The day after the April 11 provincial budget, SOLS was told that its operating funding of $3.3 million was being cut 50%. Faced with the loss of half its funding, it announced that the delivery service would end April 26.

According to financial detail buried in the financial statements on the SOLS website, the delivery operation cost about $1.3 million a year. The SOLS operation serviced reciprocal agreements between libraries such as the Libraries in Niagara Cooperative (LiNC) network used by five local libraries in Niagara.

SOLS was created in 1989 by the province to facilitate cooperation between libraries. It grew out of an amalgamation of regional library systems that themselves had provided support and development services to the libraries in their regions. SOLS covers 206 municipalities from Windsor to the Quebec border and north to Muskoka.

There is a counterpart agency to serve northern Ontario called OLS North. Its funding of $1.6 million has been cut by 50%, too. That means the province will no longer pay for inter-library loans in northern Ontario, either.

The elimination of these inter-library loans will be particularly tough on smaller libraries. Their patrons have been able to draw on a larger pool of books.

Among those affected by the ending of the SOLS delivery operation are local book clubs. When a book club identifies a book selection, librarians have helped source copies of that book from across multiple libraries.

“The people” use libraries

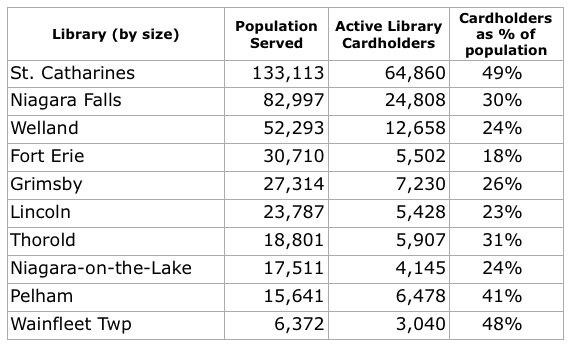

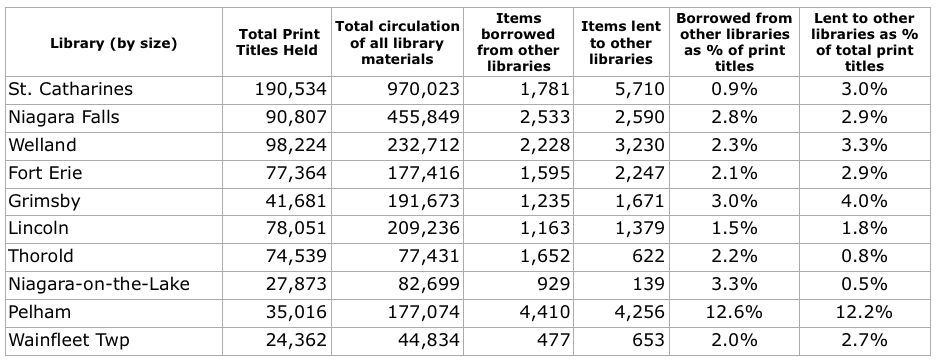

The Ford government almost sounds like Communists when they talk about “your Government for the People.” Libraries are one of the most common touch points with government services. Across Ontario, 4.5 million people, on average 33% of the population, hold a public library card. It’s not about big cities or small towns. From the Ontario government’s open data website, I compiled the statistics for libraries in the Niagara region. The largest community, St. Catharines, has 49% library cardholders. The smallest community, Wainfleet, has 48% cardholders (see table).

Who pays for libraries

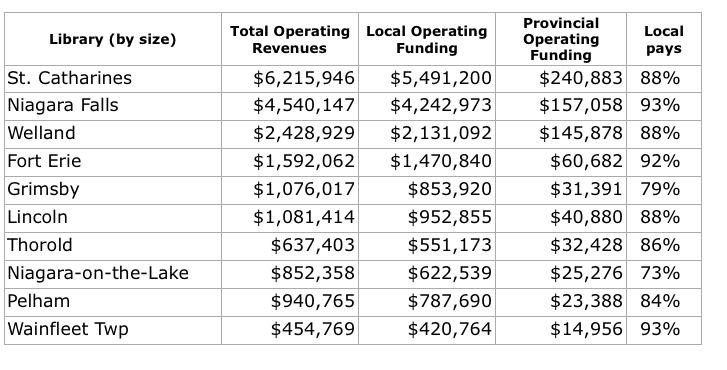

Local governments fund on average 93% of the budgets of libraries, totalling $653 million in local funding across Ontario. In Niagara, local funding provides 73% to 93% of library operating revenues (see table).

Across all Ontario, the province provides only $27 million for libraries – less than 2% of the $1.5 billion budget of the Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport, which is the ministry involved. Most of the provincial funds go to local libraries based on population.

Digging into the (budget) book

I’ve spent two days researching the library cuts, including reading the 382-page Ontario budget delivered April 11 by Minister of Finance Victor Fedeli. It’s not exactly an action novel, but there are bad guys (the previous government “spending $40 million a day more than they were taking in”), there is a monster (provincial debt of “$347 billion, or about $24,000 for every man, woman, and child in the province”) and there is hope for salvation (finding savings of “about eight cents for every dollar spent.”)

In finding its overall 8% savings, some ministries like Agriculture had their budgets chopped by 20% (sorry, farmers, but surely you will still vote Tory). The folks at Tourism, Culture and Sport got a little haircut overall. In looking for where to “save”, the fastest, easiest way to cut spending is to reduce transfer payments to agencies such as the 50% cut to SOLS.

Needless to say, the Minister of Finance talks about all the new spending (dental care for low-income seniors, mass transit, etc.) but doesn’t provide lists of which programs or agencies are being cut. When it comes to libraries, the so-called base funding from the province for individual libraries will remain intact. In fact, those amounts have been frozen for almost 20 years and have not increased with inflation.

Minister of Tourism, Culture and Sport Michael Tibollo issued a statement on April 18 on library funding, trying to emphasize the point that it is some arms-length agency (SOLS), not your local library, that has been cut.

I did wonder how Tibollo’s ministry spends $1.5 billion, so I looked at the expenditure estimates. It turns out that almost a third of that big number – $484 million in 2018 – are cultural media tax credits (think video games and movies filmed in Ontario with American actors). I guess it would not have been a good soundbite to say something like “We’re cutting support for libraries so we can fund more video games.”

Leveraging tax dollars

Frankly, if Minister Tibollo isn’t sure what it is that SOLS does, it’s probably not entirely his fault. I’ve studied SOLS website and read its financial reports, but there is so much jargon it’s hard to be sure. In addition to the delivery service that is being ended, among other things SOLS negotiates and coordinates bulk discount purchases of online library products such as e-books and databases.

Organizations that represent special interests make pre-budget submissions to governments. I looked at the joint submission of the Ontario Library Association (OLA) and Federation of Ontario Libraries. While it is a fine document in terms of its advocacy for libraries and listing of how libraries serve the people (broadband access etc.), it seems tone-deaf in terms of educating a government that is trying to reduce overall spending in order to battle the deficit monster.

I do understand that provincial funding to libraries has been frozen for 20 years. But that just suggests that the library association’s story was not well told or well received by previous governments, either.

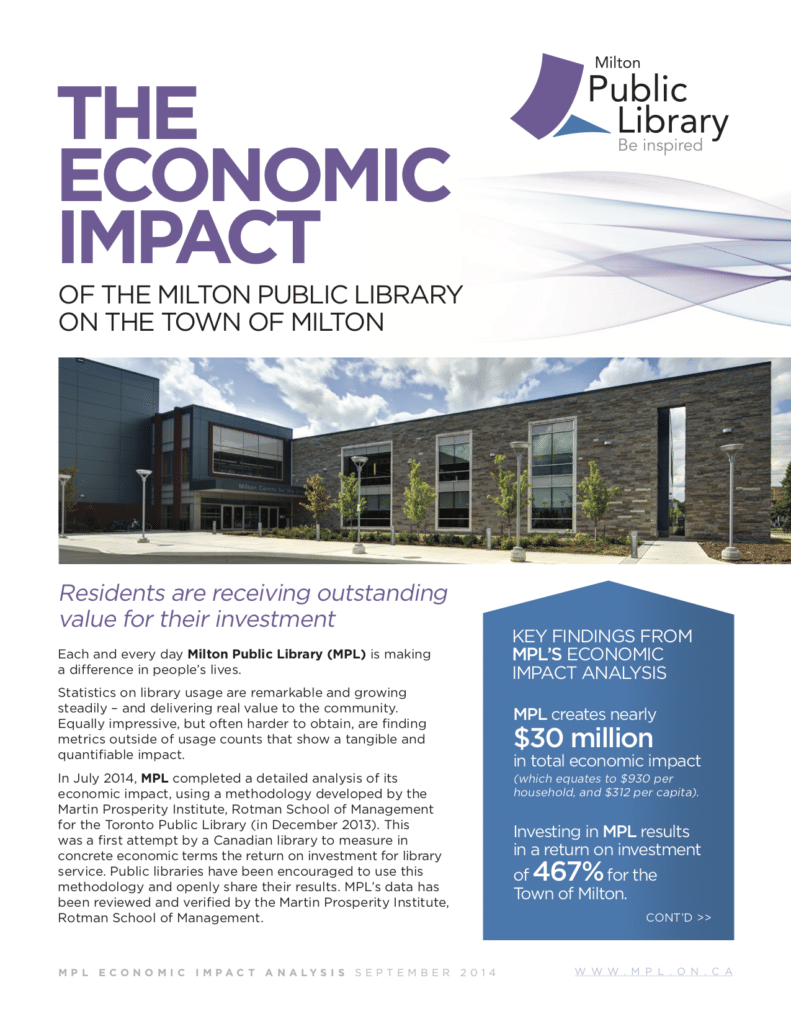

The OLA submission does reference the economic impact studies that have been commissioned by several local libraries to quantify the value in dollar terms of their funding. Every dollar invested in public libraries generates $5.67 in direct economic benefits in Milton, for instance. Libraries in Stratford, London, Pickering, Vaughan and other municipalities have done these studies, modelled on the methodology developed for the Toronto Public Library in 2013 by the Martin Prosperity Institute, a research centre at the Rotman School of Business at the University of Toronto.

You can imagine that local politicians, faced with their own challenges to control spending to keep taxpayers happy, have at times been tempted to cut library funding. These local economic impact studies help to illustrate that there is a return on investment.

Given that it’s no secret that the Ford government is on a “stop the waste” mission, probably a better pre-budget submission would have emphasized how local libraries have found ways to improve efficiencies, especially with examples of technological improvements.

Frankly, it would have been credible to claim that the $4.6 million in funding to SOLS and OLS-North helps leverage the effectiveness of the $653 million spent by local governments.

The local versus provincal balance

We live at a time when governments are wrestling with how to control spending. In areas such as health care and education, there is a move toward centralization of administration – consolidation to provide more efficiency is the Ford government mantra.

Libraries are local entities. Because they are primarily funded locally, there is local control and local focus. However, they should be encouraged to cooperate and share with other systems to help reduce the collective cost burden. And, inter-library loans provide more even access to library materials, especially for smaller communities.

Just like it takes some creativity to make federalism work, we need to encourage more collaboration across Ontario.

Perhaps the province should stop providing its funding based only on population. Perhaps it should instead reward other metrics such as how much funding is provided locally or how much inter-library lending is being used. For instance, the Niagara library co-operative was established in 2010, but some libraries such as Niagara Falls had held off on participating.

I don’t know enough to say whether the SOLS book delivery operation is as cost effective as it could be. I’ve seen instances in business where long-established operations fail to adapt to new technologies and to seek cost savings.

No operation should assume that its funding is secure forever. Taxpayers no longer are willing to accept mindless deficit spending. Therefore, SOLS has an obligation to take a hard look at its operations.

A simple book lending analysis

According to SOLS, it employed 24 drivers (full time, part time and occasional) who in 2018 drove almost 1 million kilometres to deliver over 710,000 packages to 153 main library branches across southern Ontario. By my calculation, at a cost of $1.3 million that works out to a delivery cost of $1.83 per book on average. Even if the cost per book going both ways was $3.86, that’s still a lot less expensive than a library buying and shelving the book in its collection.

I tried to do a mini-analysis of how many books were borrowed between libraries based on the 2017 self-reported information in the provincial database. My compilation and analysis may be flawed. In the table below, I report some of the information from 2017. I also invented two ratios to show the number of items borrowed from other libraries as a percentage of a library’s total print titles — ranging from under 1% to 12% in Niagara. The other ratio is my “sharing is caring” calculation – the percentage of items loaned to other libraries.

Hope for LiNC service in Niagara

Updated May 21, 2019

The NOTL Library is resuming inter-library lending within the Niagara region through the Libraries in Niagara Cooperative (LiNC), which had piggybacked on the SOLS delivery service.

About 8% of books borrowed in NOTL in 2018 actually came from other libraries in the Niagara region. NOTL’s total circulation in 2018 was 100,941, including 5,573 e-resources (e-magazines, e-books and e-audiobooks). There were 7,421 items borrowed from LiNC libraries in 2018 (7.78% of total circulation).

There were also 573 items borrowed through the provincial inter-library loan system in 2018.

Links to local media coverage

| Date | Media | Link to article |

|---|---|---|

| June 6, 2019 | St. Catharines Standard | Libraries unsure how much inter-library loans will cost by Karena Walter |

| May 20, 2019 | St. Catharines Standard | Libraries reviving local book loan program on own dime by Karena Walter |

| April 23, 2019 | St. Catharines Standard | Delivery service for libraries’ books shelved by Karena Walter |

| April 30, 2019 | Niagara Now / The Lake Report | Province tells libraries to send books via Canada Post by Kevin MacLean |

| May 2, 2019 | NOTL Local | Options being considered to fund library service by Penny Coles |